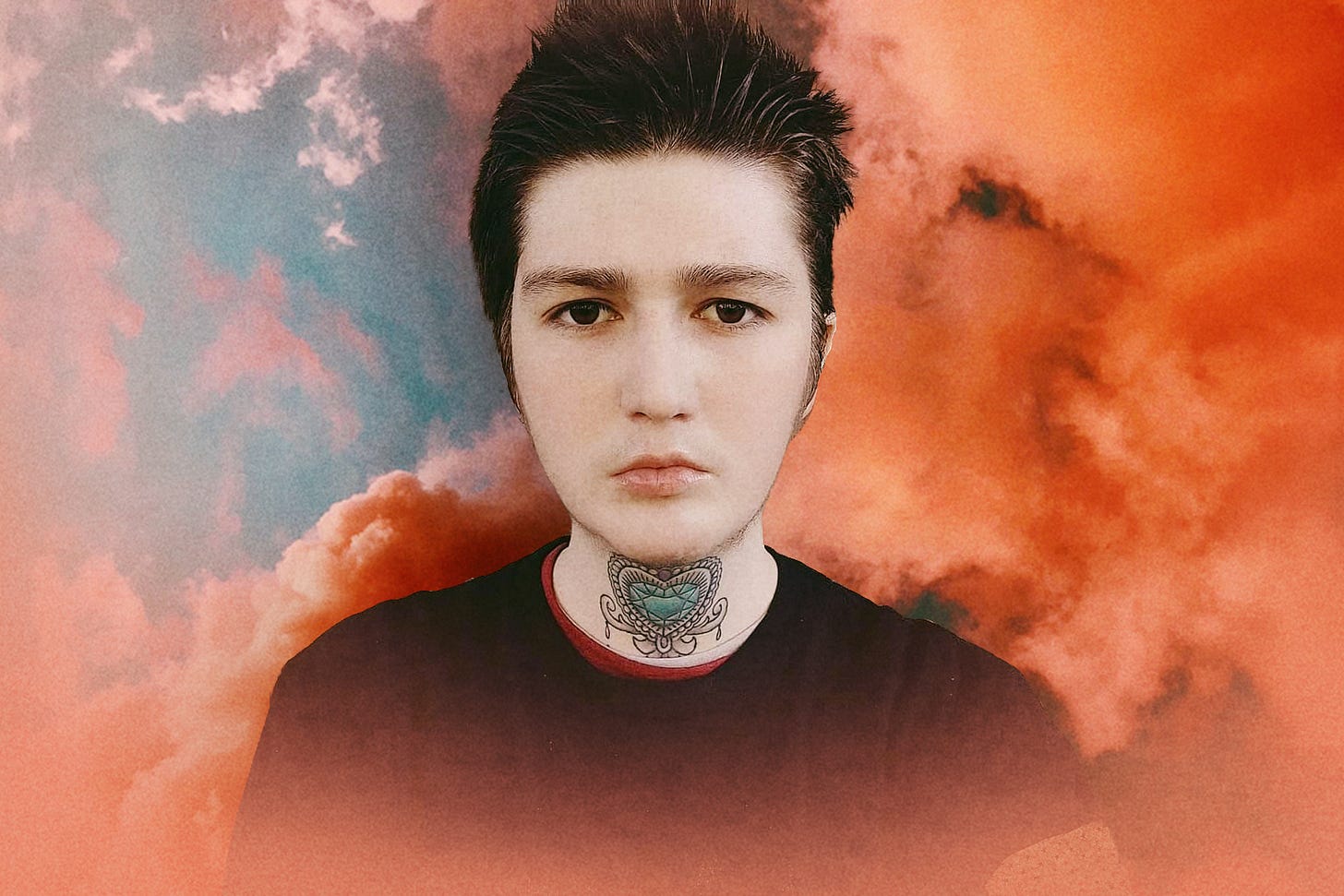

Yarden Silveira: The Trans-Origin Story

Yarden Silveira, a young detransitioner believed to have taken his own life, had every vulnerability stacked against him. Here, I examine those vulnerabilities.

A few weeks ago, I published The Tragedy of Yarden Silveira in City Journal on Detransition Awareness Day. It recounted the life of a young detransitioned man who is believed to have died by suicide after struggling to get help for severe complications from genital “sex reassignment” surgery.

The City Journal article focuses on Yarden’s experiences with the healthcare system—the long line of professionals who failed him, and the irreversible harm they caused. But it only briefly touches on what came before: the formative influences that shaped Yarden’s thinking and led him to adopt a trans identity. This article is meant to supplement that reporting. I encourage readers to read the original article for the full narrative.

I’ve been reporting on trans issues for nearly three years. It was detransitioner stories like Yarden’s that led me to become a journalist. In that time, I’ve come to recognize the vulnerabilities that make some young people especially susceptible to adopting a trans identity.

This article will take a closer look at those vulnerabilities. I’ll share excerpts from Yarden’s writing, offer additional context, and explore the broader cultural, medical, and psychological forces that shaped his story—and continue to shape the stories of other at-risk youth like him.

Yarden had every vulnerability stacked against him. He struggled with emotional issues and a difficult home life from an early age. He was autistic and young—factors that contributed to his naivety, black-and-white thinking, and identity confusion. He was also gay and exhibited gender nonconformity, traits closely associated with a higher likelihood of trans identification.

He entered adolescence at the worst possible time: the “transgender tipping point” in 2014, when trans narratives gained mainstream traction and biological explanations for trans identity became widely promoted. These ideas offered a powerful cultural script to adolescents in distress—and youth trans identification began to soar.

With the prevailing gender-affirming model of care in the U.S.—in which affirmation, not exploration, is the standard—the inherent authority of physicians, the absence of care pathways for detransitioners, and the callousness of more than a dozen doctors he encountered, it’s hard to imagine Yarden’s story ending in anything but tragedy. And sadly, it did.

Early Childhood Difficulties

Yarden Silveira, born in 1998, grew up in California—a national leader in facilitating youth gender transition and the first state to declare itself a sanctuary for minors seeking such interventions. His mother was 22 when she had him and raised him on her own in a modest household with his two younger sisters. His biological father was largely absent, and his stepfather, who was briefly present, was described by Yarden’s aunt as “abusive.”

From an early age, Yarden showed signs of emotional distress. He was often angry, anxious, and prone to sudden outbursts. His mother sought help early; he began therapy at age five and cycled through various psychiatric diagnoses throughout childhood, including ADHD, OCD, and oppositional defiant disorder, before finally being diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome at age ten.

Coming Out Gay and Gender Nonconformity

Historically, the majority of young people presenting to gender clinics were boys, and most of them were homosexual. Childhood gender nonconformity—traits, preferences, and behaviors atypical for one’s sex—is common among people who grow up to be gay. For some, this can be deeply distressing.

Before the adoption of the gender-affirming model of care, clinicians practiced “watchful waiting.” Most children eventually desisted from a trans identity and grew up to be healthy gay adults. Today, most youth are no longer given that opportunity—they are instead “affirmed” in a trans identity and often steered toward medicalization.

Yarden recognized he was gay from an early age:

“When I was 9 years old, I simply thought I was gay.”

His mother’s side of the family accepted him, but his relationship with his father’s side was strained by their strict religious beliefs. At 13, he posted a conversation on Facebook with his paternal grandmother in which he told her about his sexuality. She replied that, according to the Bible, being gay was a sin. The exchange ended with Yarden removing her as a friend. This rejection likely deepened his discomfort with being gay.

From a young age, Yarden also displayed gender nonconforming traits. His aunt recalled that although he played with traditional boys’ toys—often lining up toy cars in the characteristic autistic fashion—he also enjoyed playing with baby dolls and was very nurturing.

"I have always enjoyed femininity over masculinity."

"I'm already androgynous as it is."

Being both gay and gender nonconforming made Yarden more vulnerable to transgender narratives. In today’s climate, activist and medical organizations increasingly conflate gender nonconformity with being transgender. As a result, it’s easy for young people to misread sex-atypical traits as evidence that they were “born in the wrong body.”

Gender ideology is a belief system rooted in sex-based stereotypes. It holds that if you exhibit enough traits commonly associated with the opposite sex, you may actually be the opposite sex on the inside. Yarden seemed to believe, at one point, that sharing certain emotional experiences common among females was evidence that he must be one.

"What even is being a woman? I don't know. It feels like fear when I walk alone at night or through groups of boisterous males by myself. It feels like powerlessness when I get ignored and talked over. It feels like frustration, sadness, failure when my body does not look thin and beautiful. It feels shameful to show this body to others, because it is not perfect."

In one of his final posts, Yarden described seeing a happy gay couple on the subway and acknowledged that internalized homophobia had played a role in his decision to transition:

"You just really wanted to escape the label."

A 2021 survey of detransitioners found that internalized homophobia was a common reason given for transitioning. For many, adopting a transgender identity is not about becoming their true selves, but about escaping who they are.

Autism and Youth

Today, mild autism is increasingly prevalent among those who self-identify as transgender. Some gender clinics report that up to 35% of patients exhibit moderate to severe autistic traits, and even one clinic has found that nearly half had formal autism diagnoses.

Yarden came to recognize that autism had played a significant role in his decision to transition:

"Maybe if I didn’t have autism—maybe if my brain wasn’t so defective—I would have caught on before it was too late."

His autistic traits shaped many aspects of his life: difficulty socializing, identity confusion, and intense fixations. Like many on the mild end of the spectrum, he spent significant time online and was drawn to social justice spaces—environments where transgender narratives are widely promoted.

"I never had friends, not even in elementary school."

His mother confirmed that, as a child, he was often alone, but his obsessive interests kept him occupied. Autistic “special interests” can become all-consuming, often shaping one’s sense of identity. When transgender narratives entered the picture, that identity took hold. He spent much of his time online researching and writing about his experience as a “transgender woman” through Tumblr blogs and personal websites.

At 18, new special interests emerged—each quickly becoming central to how he saw himself. He developed a fascination with genealogy, tracing his family roots to Cherokee ancestry on his mother’s side and Russian heritage on his father’s. At the time, he went by Emily Nashoba Dykes, incorporating Nashoba, a Choctaw word meaning “wolf.”

When he discovered he shared ancestry with Joseph Stalin, it became another fixation. He legally changed his name to Emily Galilahi Jugashvili—adopting Stalin’s birth surname and the Cherokee word Galilahi, meaning “attractive woman.” He also sometimes went by Emily Halona Stalin, with Halona meaning “fortunate” in Zuni. During this period, he became involved in social justice activism, joined the Communist Party, wrote political essays, and even self-published a 36-page book titled A People’s History of the Soviet Union.

Later, his fixation on religion led him to convert to Judaism online, despite having no apparent Jewish background. Taken together, these rapid and dramatic shifts in identity pointed to a deep instability in his sense of self, which he later came to recognize.

"I wish I had the knowledge that I have today. I was a confused kid with no identity. I wish I could have done everything different, but it’s too late now."

As an 18 year old, he had a sexual encounter with another male that went wrong, that further limited his ability to trust others. Despite his solitary nature, he longed for connection and was deeply sensitive to rejection.

"What hurts me the most is the loneliness and the inability to find a partner. I can't have a normal sex life… I just wanted friendship and love."

During detransition, as Yarden began to reject the beliefs that had once led him to transition, it became clear that—like many autistic individuals—he had interpreted language literally. His posts reflect the painful realization that becoming a woman had never been possible.

"It isn’t possible to biologically transition from one sex to another, which really smacked me in the face when that reality became clear to me."

He also came to recognize how naive he had been—and how much he had trusted the medical system.

"My doctors and therapists said it was possible to change genders and even recommended that I transition. Given how naive I’ve always been, I genuinely believed them and started transitioning at 15. Why wouldn’t I believe them? I had no reason not to trust them."

Though he was legally an adult when his surgeries took place, the process had been set in motion at 16, when he told his mother he planned to get a vaginoplasty as soon as he turned 18. It would take another year before his first surgery, just after his 19th birthday.

Many detransitioners who began medical transition shortly after turning 18 don’t receive the same sympathy as those who transitioned as minors—but they should. The prefrontal cortex, responsible for executive functioning (decision-making, planning, emotional regulation), continues developing into the mid-to-late twenties. Because this part of the brain isn’t fully mature in adolescents, they are more prone to impulsive decisions, risk-taking, and difficulty anticipating long-term consequences. In autistic individuals, research suggests the prefrontal cortex may develop differently—further impairing executive functioning and increasing vulnerability to poor decision-making.

The Transgender Tipping Point and Cultural Scripting of Distress

How we interpret psychological distress is shaped by the cultural narratives around us—a process known as the cultural scripting of distress, in which internal suffering is filtered through the frameworks available in one’s environment.

Humans are meaning-making creatures. When we’re in pain—especially the kind that is diffuse or difficult to name—we look for explanations. Adolescents are especially susceptible to this, as they’re actively forming their identities while navigating intense emotional shifts. The cultural environment around them plays a significant role in how they come to understand themselves.

"I wanted to be a woman since I was 15."

Yarden entered adolescence as transgender narratives were gaining mainstream visibility. He was 15 in 2013, as cultural, political, and legal shifts set the stage for what would come to be known as the “transgender tipping point” in 2014.

Major LGBT organizations, anticipating the legalization of same-sex marriage, had begun shifting their focus and promoting “transgender rights” as the next civil rights frontier. Mainstream media followed suit. Television, books, and news coverage increasingly normalized transgender identities, especially among youth. Between 2010 and 2015, several teen-oriented shows featured trans-identified characters, including Glee, Degrassi, and The Fosters. The successful Netflix series Orange Is the New Black, which featured a trans-identified character, was also popular among teens. The reality series I Am Jazz, centered on a trans-identified child, averaged 1.3 million viewers per episode. When I asked specifically about I Am Jazz, Yarden’s mother confirmed they had watched it together.

Transgender narratives were especially prominent on Tumblr—where Yarden maintained multiple accounts—particularly between 2010 and 2013, often referred to as its “trans heyday.”

In 2014, at age 16, Yarden fully socially transitioned. He changed his name, pronouns, and appearance, and successfully advocated for those changes to be recognized at school. That same year, California—where Yarden lived—became the first state to allow students to access bathrooms and sports teams based solely on self-declared identity, sparking national debate.

With the mainstreaming of transgender identity in media and culture, it’s not hard to see why youth trans identification began to soar during this period. For Yarden, these narratives were a powerful influence during a formative period and played a significant role in how he interpreted his distress—contributing to his decision to adopt a trans identity.

Bionarratives and Medical Authority

Alongside cultural forces, the medical and scientific establishment played a key role in shaping beliefs about transgender identity. Doctors and researchers began searching for biological explanations—and many people, including Yarden, found those ideas persuasive.

“A trans woman (such as myself) was born with a male body, but she has always had her female brain. Literally born with a female brain.”

Yarden wrote this in 2016. When I asked his mother about it, she confirmed that the “female brain” narrative had been a major influence on him. His literal-mindedness—likely related to his autism—made such explanations especially convincing. But this wasn’t unique to him. The idea gained traction because it was promoted by medical authorities and widely reported as settled science.

The 1980s saw two major developments in psychiatry: the introduction of the gender identity disorder (GID) diagnosis in the DSM-III, and a growing belief that brain imaging could reveal biological causes for mental distress. But despite decades of research, no consistent biomarkers have been found. That’s because, unlike many medical diagnoses, most DSM-defined disorders do not explain the source of distress; they merely classify its presentation. The same limitation applies to GID, now called gender dysphoria.

Between 2014 and 2017—around the time Yarden was researching these topics—brain studies on trans-identified individuals peaked. Some findings suggested that certain brain regions in trans-identified males resembled those of females, fueling the “brain-body mismatch” theory. These studies received widespread media attention.

What got far less coverage were the follow-up studies that debunked the findings after controlling for sexual orientation and hormone use—both of which affect brain structure.

The belief in a biological basis for being transgender can deeply influence how individuals understand themselves. When that belief is reinforced by medical professionals—figures seen as trusted authorities—it carries extraordinary weight. Under such influence, both young people and their parents may come to view medical intervention not as an option, but as the only responsible course of action to treat what they believe is a biologically determined condition.

Yarden had easy access to all four surgeries he underwent, as each was covered by California’s state insurance, Medi-Cal, which relies on WPATH standards in its coverage decisions. With insurers classifying these procedures as “medically necessary” and gender-affirming clinicians clearing the path, it’s not hard to see how someone like him could undergo so many operations in such a short span of time.

To a layperson, the phrase “medically necessary” may sound like an imperative. But in insurance terms, it simply means a treatment meets certain criteria for coverage—not that it’s always the best or only option.

Read more: Transgender Brain Studies Are Fatally Flawed

Rigid Thinking and the Gender-Affirming Model of Care

Black-and-white thinking—also known as rigid thinking—is especially common in adolescents, autistic individuals, and those with certain mental health conditions. It can lead some to believe that all of their distress stems from being transgender, and that medical transition will resolve it.

The gender-affirming model of care, first established at Boston Children’s Hospital in 2007, quickly spread across the U.S. Over time, the previous standard of “watchful waiting” gave way to an affirmation-only approach. In gender-affirming therapy, the therapist does not question or investigate the source of a patient’s distress but instead validates the declared identity. The underlying (though incorrect) assumption is that people are born transgender in the same way they can be born gay—and that to suggest otherwise is considered “conversion therapy.”

As a minor, Yarden began seeing a gender-affirming therapist who, according to him, encouraged his transition. In hindsight, he saw this as a profound betrayal.

“I consider everything she did to me to be psychological abuse.”

At 17, he received a prescription for cross-sex hormones from a Fresno clinic. In many clinics, patients can access hormones after a brief consultation—sometimes as short as 30 minutes.

Surgical intervention often follows the same logic. The role of the gender-affirming surgeon is not to evaluate medical necessity, but to confirm that the patient meets basic administrative criteria—usually a letter from a gender-affirming therapist—before proceeding.

In a short span—between the ages of 19 and 21—Yarden underwent a series of procedures: penile-inversion vaginoplasty (with follow-up revisions using skin grafts), breast augmentation, a second vaginoplasty using a section of his colon, and facial feminization surgery. His writing reveals a pattern of rigid thinking. Even as serious complications emerged, he remained fixed on the belief that the next procedure would finally bring him peace. Before undergoing facial surgery in the summer of 2019, he wrote:

“If this one surgery is a massive success, then I wouldn't have wasted so many years of my life for nothing. I wouldn't have lost all my friends and the vast majority of my family for nothing. It would all be worth it!”

He was not alone in this mindset. It’s a familiar experience among those with gender dysphoria and body dysmorphic disorder (BDD): once one perceived flaw is addressed—surgically or otherwise—another takes its place. The focus of distress simply moves to a new target. See examples highlighted by detransitioner Exulansic: [Example 1, Example 2, Example 3, Example 4].

Unsurprisingly, the result of the facial feminization surgery left him disappointed:

“I thought I would look beautiful, but I see myself as unattractive. This too wasn't what I had imagined.”

Just as he had once clung to the idea of the next surgery, he also clung to the idea that the next surgeon might finally fix what had been broken:

“I want to find a surgeon who can help me, but they always end up causing more damage to my body.”

Having already sacrificed so much—his health, relationships, and sense of self—it took time for Yarden to accept that continuing down this path was not helping. But by then, the damage had been done.

As his complications became increasingly dire, and not one of more than a dozen doctors he turned to would help him, Yarden is believed to have taken his own life at just 23 years old. This was 2021—just before detransitioners began gaining broader public recognition. Had he lived, I imagine he would have become a public-facing detransitioner, campaigning for change.

Yet even today, there is no established protocol for medical detransition. No clinical guidelines. No medical billing codes. Few insurance plans cover reversal procedures. The system still offers only a path forward—not back. In a better system, the vulnerabilities Yarden carried would have prompted caution—not a fast track to harm.

This poor fucking kid. A whole life ruined and destroyed by these Mengelian fucks. It’s the banality of evil all over again. Because some boxes on some forms were ticked a young man was cut up by “doctor” after “doctor”.

I can’t read any more about this subject for a while, I get so angry.

Thank you for sharing this important story. And thanks for discussing the link to autism.

"Today, mild autism is increasingly prevalent among those who self-identify as transgender. Some gender clinics report that up to 35% of patients exhibit moderate to severe autistic traits, and even one clinic has found that nearly half had formal autism diagnoses."

And:

"Black-and-white thinking—also known as rigid thinking—is especially common in adolescents, autistic individuals, and those with certain mental health conditions. It can lead some to believe that all of their distress stems from being transgender, and that medical transition will resolve it."

My daughter, who is trans-identified and fully medically transitioned, admitted to being autistic although it was never officially diagnosed in childhood.

We are not caring for kids and vulnerable young adults. Lack of comprehensive care and endorsement of "affirmation only" is harming so many young people and the ripple effect from that lack of real care is unmeasurable, but we see it everywhere now.